Phase 1: Train

In the early years of teaching the class, we didn’t really do much Training because we hadn’t figured out what the students needed. Instead, we did 3 weeks of abstract lectures, and then threw them right into the pool.

From a logistical point of view, getting a student to launch something for the first time is already really challenging. As we’ll talk about later, it’s emotionally and logistically complex for both the student and the instructor.

But as an instructor, you have an additional challenge: getting a whole cohort of students to run through the obstacle on roughly the same schedule and stay in sync with each other. It’s like herding a bunch of scared kittens! We’ve found that the best thing we can do as instructors is to make sure that everyone is at least starting on the same page, by introducing some fundamental concepts and skills.

Training is also helpful for giving students a preview of what they will be experiencing more fully in the later phases of the challenge. Transformative learning requires repeated exposure.

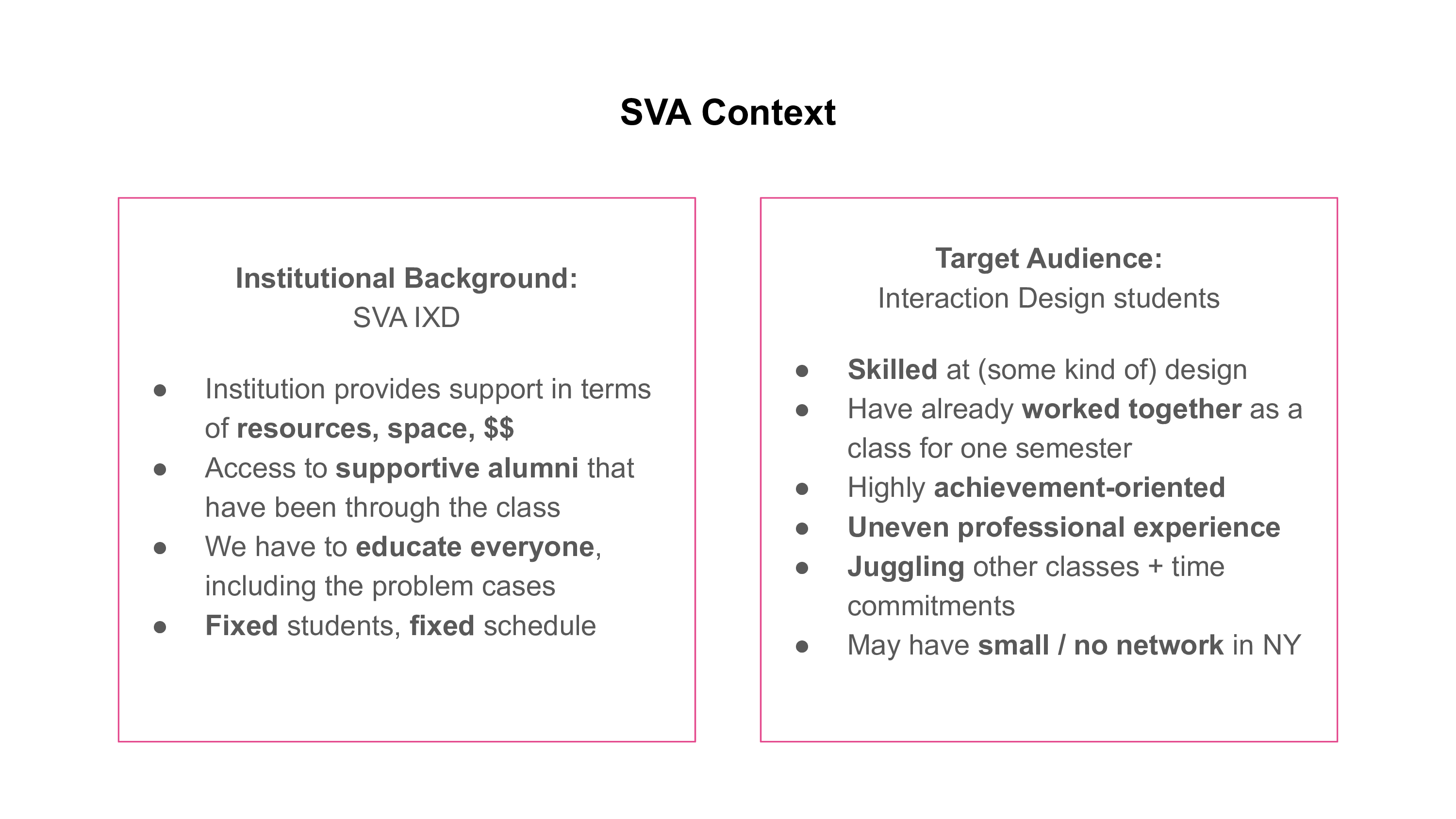

The context we're operating in dictates how we prepare the students.

What you need to cover in Train depends on the context in which you are teaching, as well as who your students are.

For our students, we center our Train phase around 3 fundamental skills.

Being an Explorer

To help our students move into an explorer (vs. an achiever) mindset, we structure the Train phase as a series of challenges (mini-obstacle courses designed to get students practicing fundamental skills while exploring their interests) and habits (tools and practices that help students in the journey ahead).

Sending Signals

We define a signal as a way to share intention, gather feedback, and identify allies: like a flare sent out into the world to find others curious about the same topic, or a flag planted in the sand to declare one's stance.

Blogposts are very common signals, which make it easier for people to find you and learn what you’re about. As we've learned in our own lives, it's very helpful to be able to link to a post we've written, instead of writing people very long emails when asking for their time.

When we first started teaching, we never thought we had to teach this to a generation that grew up online. But even though having an online identity is pretty crucial for an interaction design career, we have found that many of our students really struggle with putting their work online and interacting on networks. We came up with the Hello World! Challenge to make sure they all had at least one published story under their belts.

In fact, the Hello World Challenge is actually also the kickoff for the blogging habit we ask them to maintain throughout the semester. Asking students to blog weekly encourages them to be less precious with their thoughts and work, and to increase surface area for serendipity.

Understanding Networks

Helping our students build up a network is critical to their success not just in the class, but for their whole careers and lives.

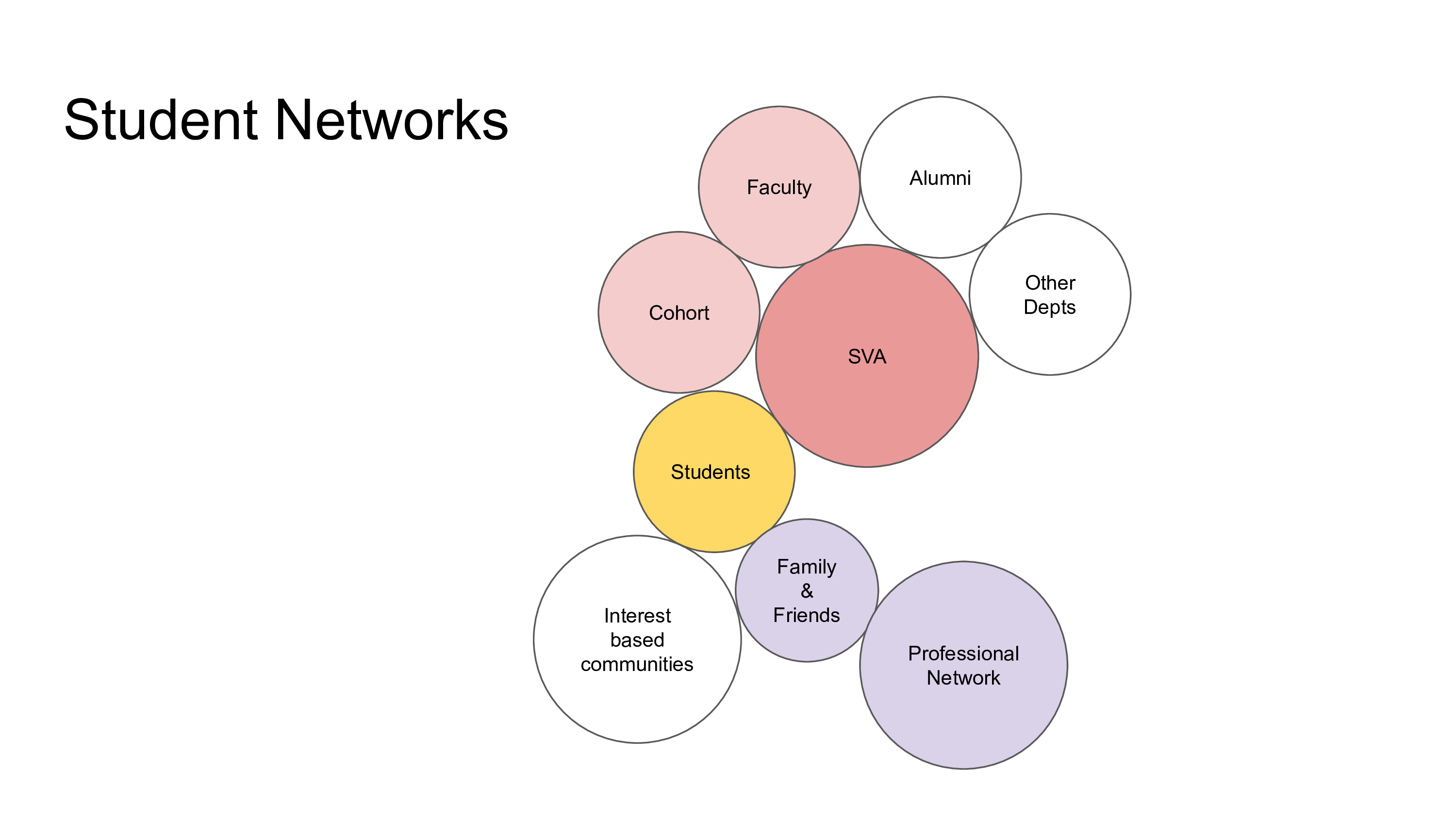

This is where the students' networks are at in the beginning of the semester. White circles are parts of their networks they may not have activated yet.

At SVA, we teach a lot of international students who are new to New York and often don’t have large networks in the city. We realized that this was making a huge difference in how they were able to engage with the rest of the class.

We're reclaiming ICOs.

Through a challenge we cheekily named Initial Community Offering, we get the students to start understanding (and building) networks by spending time with a community, then iteratively designing an offering that can serve the community’s needs. The ICO challenge familiarizes students with how networks/communities work, how to observe them, and how to give back to them—essential skills if they’re really going to design something with the community, rather than making a solution based on untested assumptions.

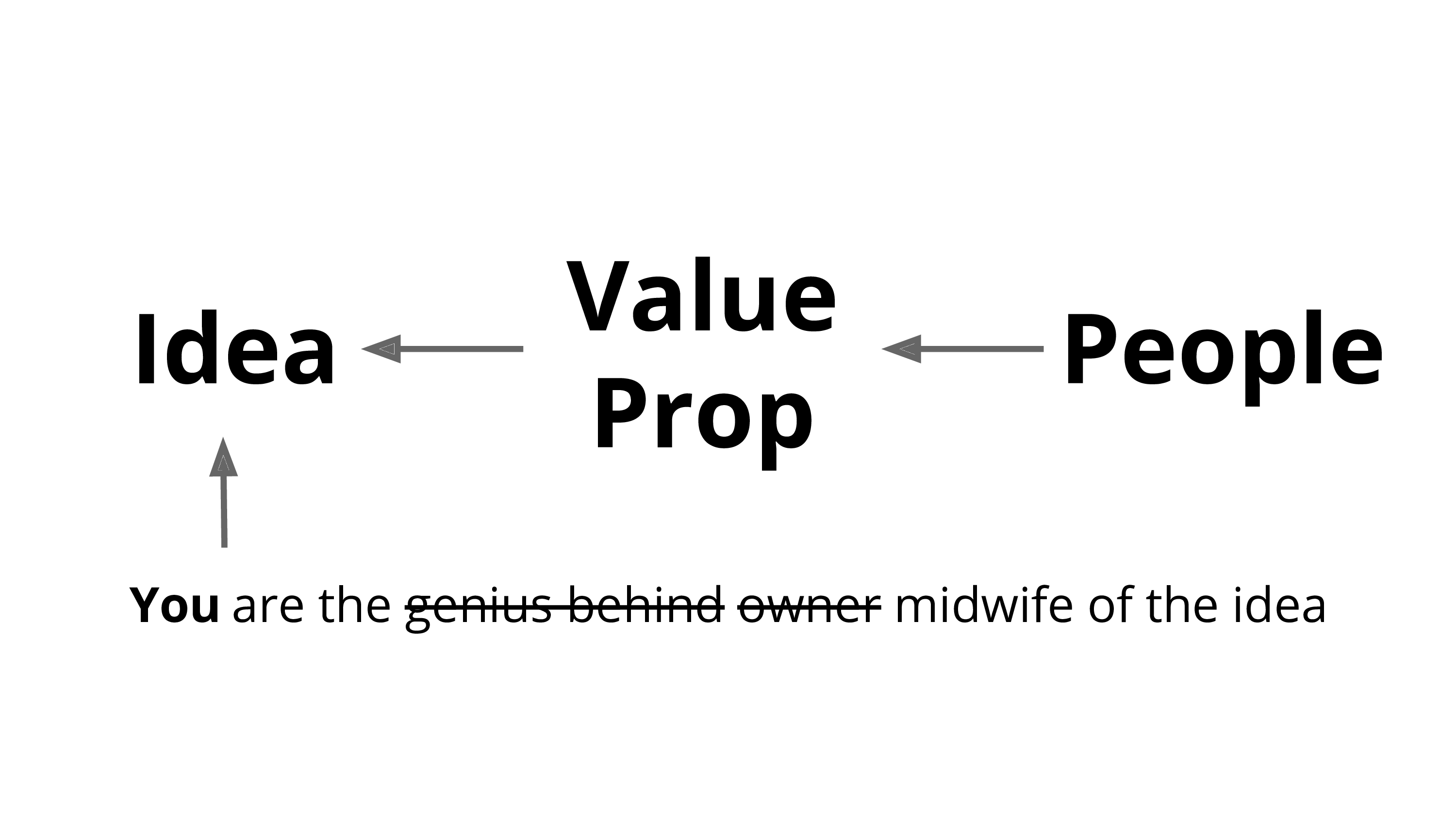

This reframe has been a helpful one for our students; there's so much media promoting the lone creative genius myth out there for designers!

In our opinion, a common affliction with the narrative around design and entrepreneurship is that people start with an idea, then define the value proposition, and then go hunting for the people who might care about it. It’s counterintuitive to start with people, but doing so reframes the exercise of design as one of deriving problems, not inventing them. This also allows us to dismantle the damaging and limiting idea of the lone wolf creative genius, and introduce in its place the concept of being a midwife of an idea birthed by the community.

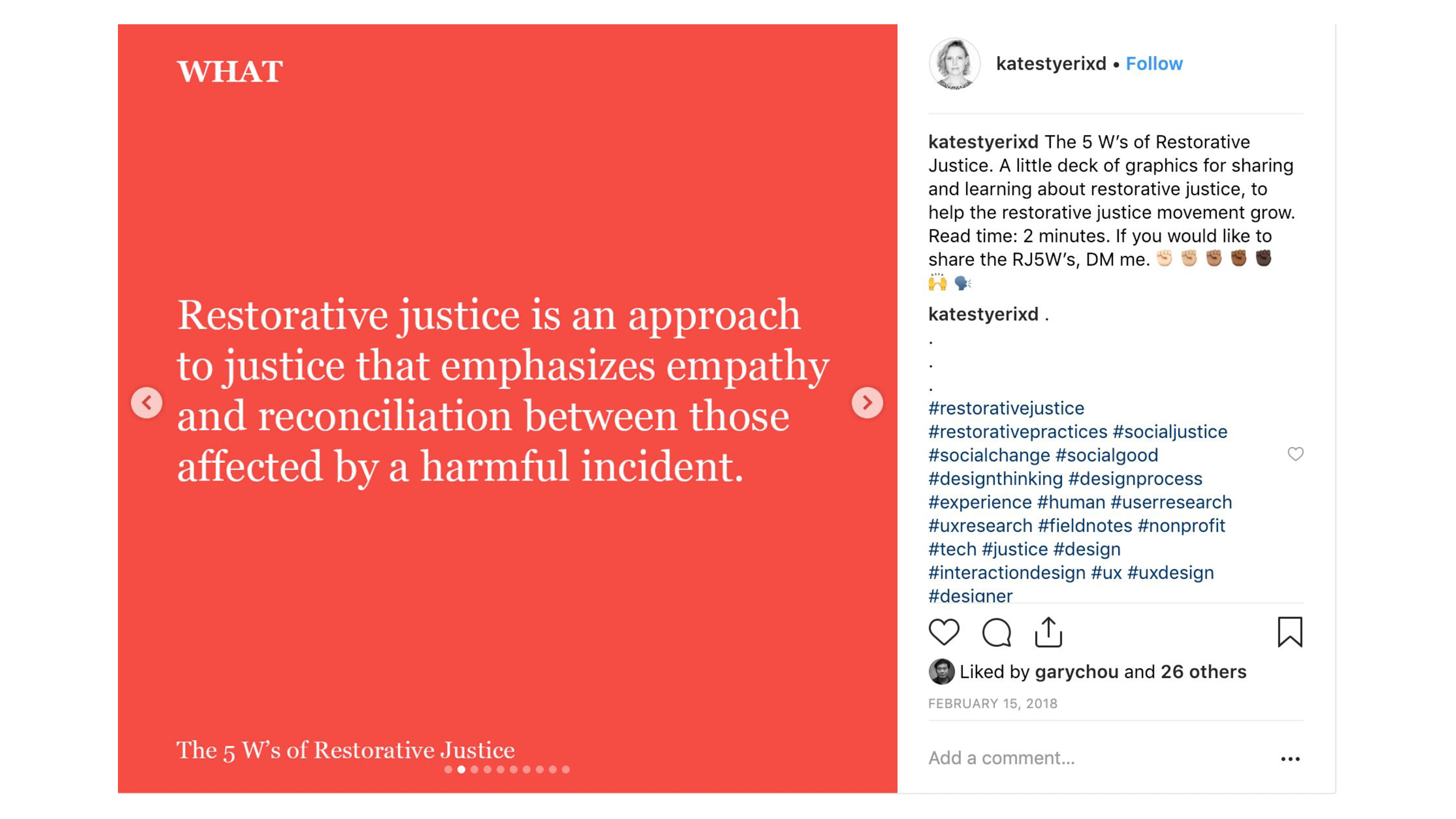

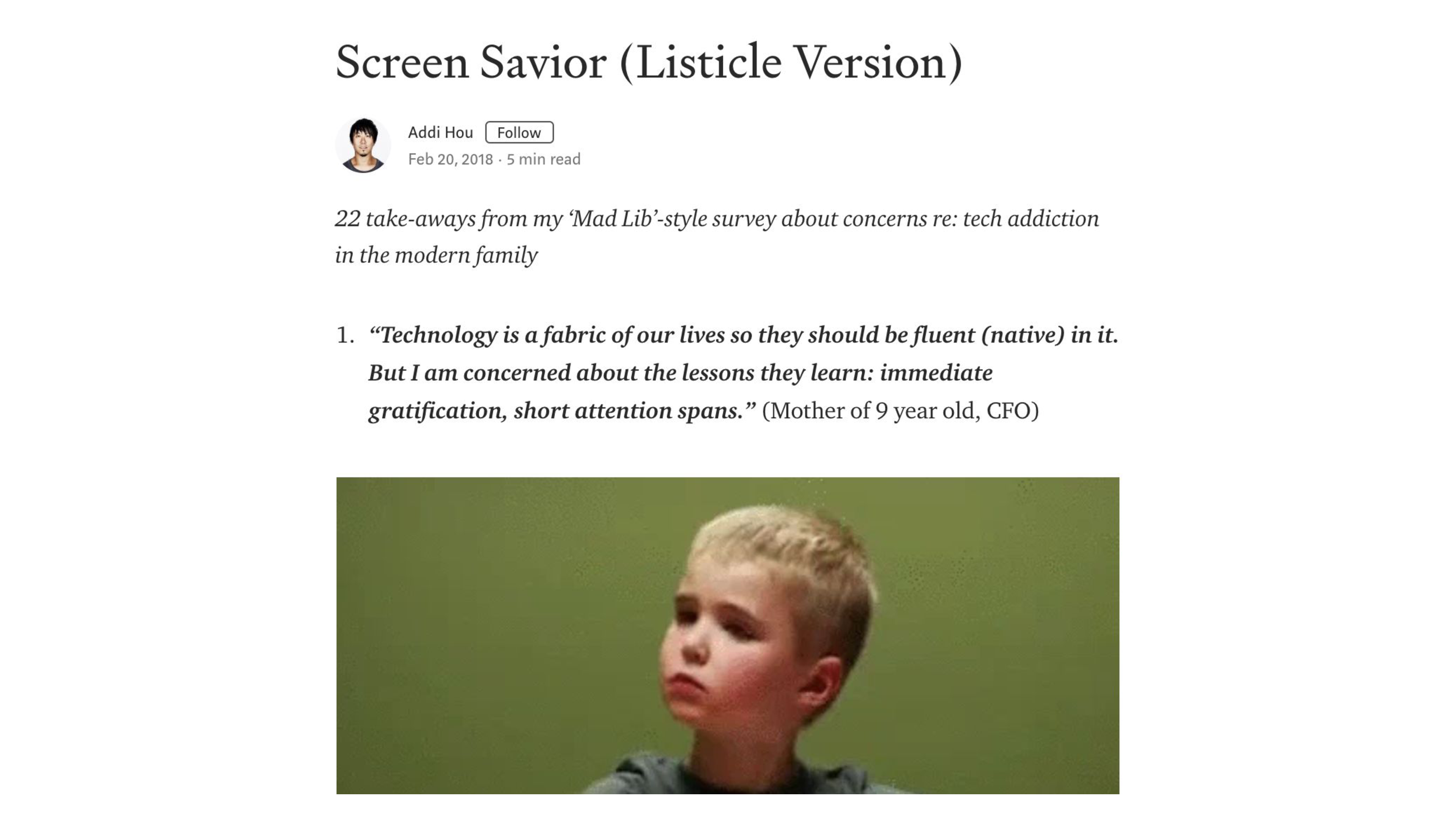

Top: an Initial Community Offering from Kate Styer to the restorative justice community. Bottom: Addi Hou's ICO on parental concerns around technology

By the time our students are done with the training phase, they have gone through one of the core iterative loops of our class:

- make something that serves as a signal

- have a conversation, and

- share back what they’ve learned as a new signal.

← How We Teach Prepare →