Working in Public

Gary: There’s some context we should set up here because it’d be a shame if people thought Entrepreneurial Design was purely about teaching people about the operational minutiae of selling a product.

There are two broader trends to consider: technology has gotten cheaper and more powerful, and so a single individual can do a lot more than he or she could 20-30 years ago. But also, because we’re all hyperconnected by networks, we’re far more aware of all the narratives happening around us. So there’s this gravitational pull towards realizing your own aspirations, most of which don’t have anything to do with your day job. People aren’t being asked to do more—they want to do more, and they can do so now.

But they haven’t been taught how to express and realize their own ideas. For one, industrialized models of education have focused on skill acquisition. Two, this is just a hard and messy thing to teach.

Chris: A key part of our course is that we ask our graduate students to work in the real world, which is very different from the speculative work that’s more common in traditional design curriculums. Currently, we require our students to use the crowdfunding platform Kickstarter because it works well in the context of launching an idea in a semester-long course.

G: Right, so instead of creating a PowerPoint of a great pitch idea or a prototype that no one actually uses, the students have to make a real thing and, in doing so, confront this question of whether it will actually work or not.

C: I like to think we’re helping them acquire a type of muscle memory for doing real projects: only through practice do you get better at hitting the launch button despite the uncertainty of not knowing whether your project is good enough. No amount of thinking and speculation can fully prepare you for the real launch process, because unpredictable and indescribable problems are inevitable.

How a creator deals with these problems ultimately shapes how good the project can be.

―Chris

If you are prepared to react to those problems and anticipate them ahead of time, that makes you a much more effective creator.

Before, if you worked as a designer in a large company, there were other people to take care of figuring out how to mail 150 packages for you. You didn’t have to know that information. But as an independent creator, you can’t just brush that off and say, “this isn’t design; I’m not dealing with it.” The whole process is part of your design.

Class of 2015’s Mikey Chen and Sam Carmichael’s The Upstanding Desk

G: But that doesn’t mean you have to actually do everything yourself.

C: Right, and Kickstarter reinforces that—it asks the students to not only define their ideas, but also invite other people to join them.

G: And this one of those things that sounds simple, but there are so many underlying things that are complicated and challenging. In order to do what you’re talking about, students need to have some online representation of themselves that they’re comfortable with. And developing and externalizing that identity has been one of the hardest parts about the course.

Students have to be willing to put themselves out there—to plant a flag—if they want to benefit from and leverage online networks. We try to ease them into it over the course of the semester with the smaller assignments and a weekly blogging requirement, but it’s been hard. Creating an online identity comes with much more anxiety than it did before.

Class of 2014 Xena Ni’s, League of Ladies: Women’s Superhero Underwear

G: Take Twitter, for instance. Five years ago, Twitter used to feel like you could carve out your own little island and play well with everyone else. But this year, we’ve had a few students express apprehension: “What if I tweet the wrong thing and ‘Angry Twitter’ comes after me?” There’s a much stronger awareness of the chaos than before.

At the same time, I think we saw more students get summer internship opportunities this year because of their public blog posts.

C: It’s less important for us to declare whether Twitter is safe or dangerous and more important to teach literacy around these online spaces—here’s why this space feels this way and here are the properties you should look for in a network that you’re investing your time in.

When the two of us started using Twitter (2008/2009), the magic was that it was big enough many people we didn’t previously have access to were on it, but small enough that it still felt like a club. Now that it’s no longer a club because literally everyone is on it, it’s less open mic-night and more American Idol. It’s a harder space to experiment in, and with less of a payoff.

Medium has and hasn’t become the new open mic-night. It’s easy for a newcomer to get the attention of established people, but it’s so public and the format of well-polished essays generates a lot of anxiety.

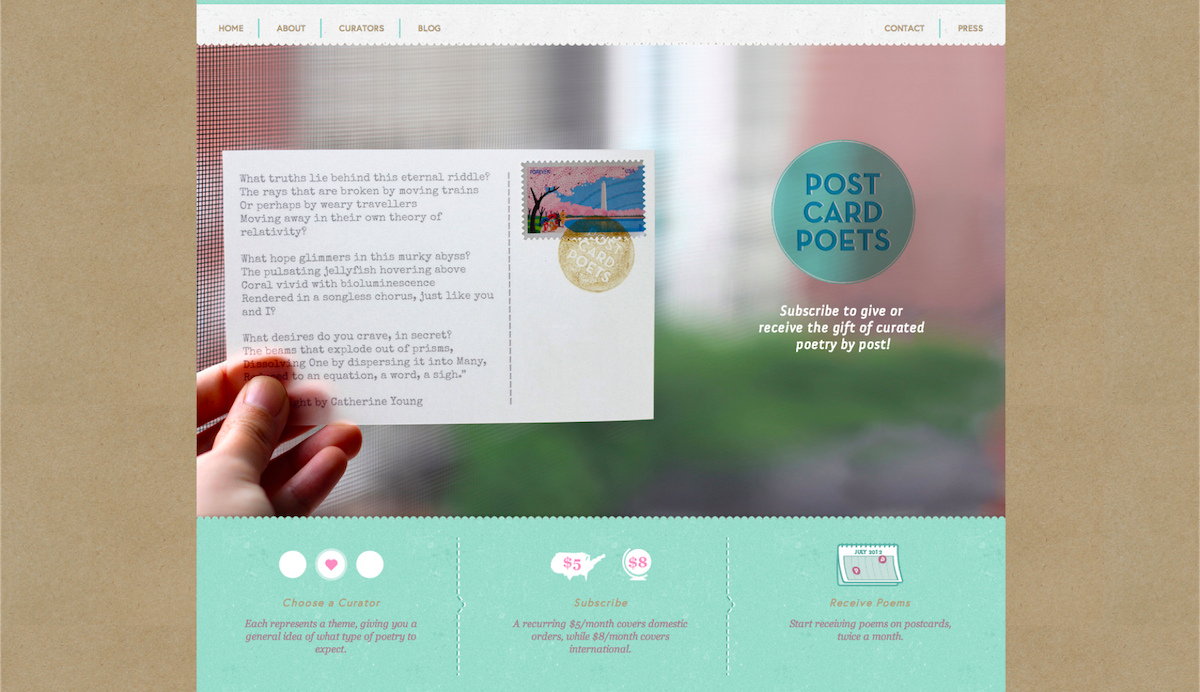

Class of 2013 Sana Rao and Nikki Sylianteng launched Post Card Poets

From Independence to Interdependence

C: One of the benefits of making the students work in the real world is that it puts all of us—the students and the instructors—on the same team. Whether the students hit their $1,000 goal is up to the world, not us. So in the course, we are their coaches and allies working with them, not grading or judging them. That’s quite alien for some of our students.

G: I think that’s been one of the most important aspects of the design of the course. It reframes the classroom dynamic, which is traditionally competitive or about seeking approval in some form. And that traditional model is at odds with how how the process of creation works: most people think a course is a single-player game whereas it’s really much more of a multi-player game.

The course is intentionally designed to get the students to involve us (and others, including their classmates) in their process and to normalize that collaborative way of working. Instead of thinking that relying on other people is a crutch, we want students to understand that interdependence is core to anyone’s success. In fact, we lean heavily on our own personal and professional networks to be speakers, advisors and supporters. We couldn’t be effective in teaching the class otherwise.

C: That’s why another major component of the course is learning how to create networks that support your work and how to maintain those networks.

G: That’s a nice way of putting it.

C: Sometimes that can come off as a very transactional thing. But networks that are robust stay robust through use—you’re giving the network things it wants, but you’re also asking it for things you want. As long as exchanges are flowing through it, the network stays alive.

As long as exchanges are flowing through it, the network stays alive.

―Chris

G: Learning to understand that you have to cultivate this system alongside the creation of your thing is also part of the challenge. Creating the thing is hard enough as it is. Back to the idea of working in the real world, it’d be hard to practice cultivating a network if you were working on a fake project.

C: Also, it really matters that the students are going through this experience together. Having a cohort just makes this process a lot easier because you have a group of people who are not your instructors and not your audience, but working alongside you.

G: The value of the cohort is that it expands the surface area of lessons to be learned. You are learning not just from your own experience, but also through observing others in the cohort. You get to learn from the different decisions they've made, the challenges they’ve run into, and how they’ve overcome those. Also, you can calibrate your progress to the others in a way that helps you push forward. It's like having a bunch of running partners.

C: It also helps because when you are thinking about your own project, everything seems hard, muddled, and you have no idea what the next step is. But for whatever reason, it's much easier to see what other people are going through and what their problems are. Giving somebody else the advice they need may actually help unblock you. Effectively, you’re just unlocking parts of your brain by tricking it to work on other people's problems.

Class of 2017 Saba Singh and David Al-Ibrahim meet with Advisor George Rohac

G: Right, everyone is much better at diagnosing everyone else's issues and strengths than diagnosing their own. There are certainly patterns that we see year after year. However, there’s usually some new different perspective or problem or approach that arises where I think to myself, “This is easy for us to diagnose only because we’re not the ones going through it.”

Every single piece of advice I’ve given has been something that I sort of stashed away in my head because I’ve known it’s something I would need for myself in the future. That’s what keeps me going as a teacher. I’m constantly building up this library of both problems and solutions, and that has helped me be a better creator.

When it actually comes down to your own problem, you approach it in a way that’s somehow objectively just dumber.

―Chris

C: Yeah, definitely. But it’s hard to take the advice. Even if you’re the one who gave it, even if you’ve given it to dozens of other people. When it actually comes down to your own problem, you approach it in a way that’s somehow objectively just dumber. It doesn’t make any sense.

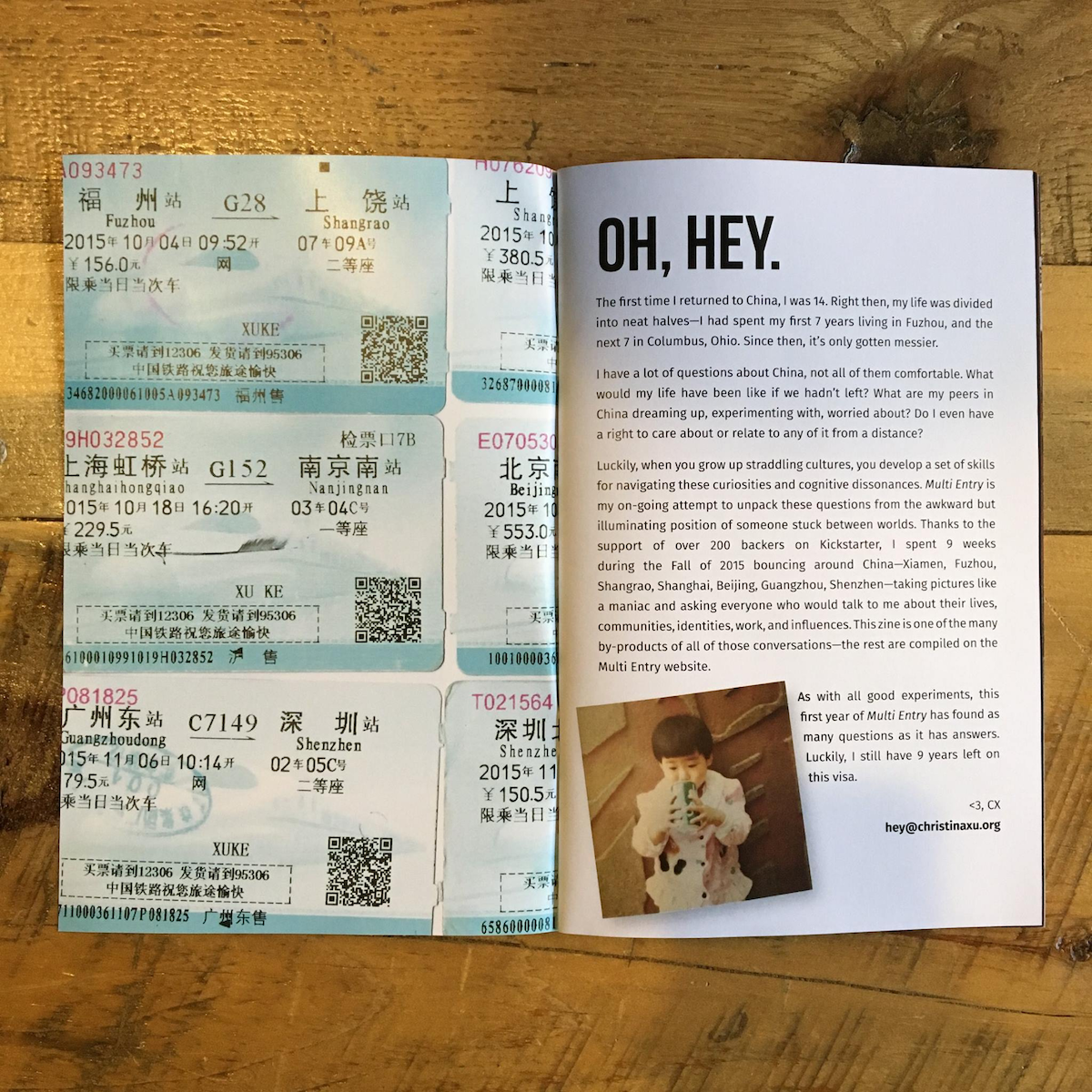

I did my Kickstarter project (Multi Entry) largely because of the course. I wanted to know how it felt to go through the process that we ask our students to go through, and to better diagnose problems that they might have.

When I was starting my campaign, I remember thinking, “I don’t have a support network, and this is really rough.” Somebody said, “You can make your own,“ and I was like, “Oh, yeah.” This was literally not even two weeks after teaching the Orbital 1K, and two months after finishing an entire semester of teaching Entrepreneurial Design. I just taught this twice! Still: hard to apply it to yourself.

Class of 2016 Datrianna Meeks’ What Would Beyoncé Say succeeded at getting Beyonce’s attention.

G: It’s because networks are still kind of invisible constructs. In some ways, we all have existing networks, and when they’re useful, we think of the person who helped us rather than the entire system. So, it’s not apparent that you need to be intentional about cultivating it.

You recreated the architecture and infrastructure of the course, too, right?

C: Yeah, so I set up the whole project in four weeks, and then I launched. The project ran for a month, so the whole thing took eight weeks, which was very tight—much tighter than our SVA course, actually.

G: And you got yourself a coach?

C: I got myself many coaches! I set up a little board of advisors which was just a loose group of people I would email updates to. I think only half of them ever read the email, but that was fine—it was more about having people who, in my mind, were holding me accountable to progress. On top of that, I had someone I met with once a week who checked in on what I was doing and made sure I wasn’t just spinning my gears.

G: Which is great to see. Not just because of the ties back to Entrepreneurial Design, but it kind of hit on all of the points that you had identified in your XOXO talk a few years ago: the false expectation that just because we now have access to things like Kickstarter and Twitter, that any creator should just magically become a jack-of-all trades.

C: One of the most important things I’ve learned in working with creators is that even if you are capable of doing all of these things yourself, that doesn’t mean you should or can do them all at once.

Even if you’re a brilliant writer, editor, and producer who somehow also knows how to market your own work, it’s really hard to bring all of those things to bear on the same project. In a lot of cases, these different roles require completely different and sometimes conflicting priorities and energies. For example, the role of the producer is to make sure something ships on time, and the role of the creative director is to dream up big ideas and point out the things that are not good enough. Those are fundamentally opposing roles. I do know a few people who can do both, but it’s extremely difficult to make that switch in your mind and not end up compromising on both sides.

G: Why do you think people try to take it all on themselves?

C: Sometimes, it’s because you don’t even understand what you’re doing yet, so the thought of trying to communicate your intent to other people feels impossible. The myth that you have to know what you are doing every step of the way is something we can help people debunk, but it’s a hard mindset to change. We’ve been taught to believe it is easier just to do it yourself.

G: Just that phrase: “Do it yourself.” That’s the problem.

C: Yeah.

G: It should be: “do it with a bunch of people who have your back.”

Chris’s zine, a reward produced for her Kickstarter campaign “Multi Entry”

Developing a Practice of Momentum

C: There is a related thread here about developing a practice of momentum: how do you maintain weekly progress or make decisions when you’re stuck? How do you work through that cycle of doubt?

I’ve come to really appreciate the process of review as a weapon for getting past the cycle of doubt and uncertainty.

―Chris

If you can build in a regular practice of checking in with other people who don’t have a direct stake in what you’re doing, that can be a way forward. It both forces you to make decisions by the time that review happens, but also allows you to get fresh perspective, which is so important when you’re in a solitary creation process. It’s so easy to just fall down a pointless rabbit hole, like how many pages is this thing going to be or what color is it going to be? At some point, you hit decision fatigue as an individual creator. That’s when review can help.

G: What are some of the ways we build in review over the course of a semester?

C: First and foremost, we encourage students to blog about what they were doing. In an ideal world, that means their classmates are going to read their posts and leave helpful comments, and maybe even other people from the Internet will read them. At a minimum, it simply makes it more likely that they’ll talk to each other in the studio.

Second, rather than having one-on-one time with each student, we organize the students into groups where they critique each other, an idea that our fellow instructor Leland Rechis came up with.

Students from the Class of 2017 chat with attendees after delivering their public talks

Third, we have three public-facing milestones—evenly spaced throughout the semester—to help pace their progress:

- The first milestone (Week 5) is to present their ideas and their questions as a lightning talk—limited to two minutes—to an unknown public audience.

- The second milestone (Week 7) is to present their nearly finished ideas—in the form of an initial Kickstarter project draft—to a network of external advisors. The advisors are all people who have experience launching creative projects, but no knowledge of the students’ work up to this point. This objective perspective gives the students an opportunity to get multiple fresh perspectives on their projects, which becomes increasingly important as the semester goes on.

- The third milestone (Week 12) is launch.

This is followed by a formal and deliberate review process (2014, 2015) that spans the final three weeks of the semester.

G: I think the reason these milestones are effective is because they aren’t really about presenting work to us, the instructors. They’re presenting to other people and normalizing this external engagement as part of their process.

A regular diet of discomfort is key to maintaining momentum.

―Gary

You have to engineer that into your process. Because, at some point as the students become more comfortable with us, we’re no longer a motivational threat.

C: Neither a threat nor an influence.

G: I think the most important change you made was introducing an ideation exercise in the second week of the semester. Historically, we didn’t help the students come up with an idea because we thought that as a bunch of creative people in an MFA program, they could just magically figure that out.

However, this is a flawed way to look at it. The ideation phase is a warm safe place—it’s too comfortable. You would stay there forever if you could.

And so you need a process to get through it. How did the exercise work?

C: The ideation exercise was about pointing out the things students should be considering as they came up with project ideas.

For example, one of the questions we asked that might have been a little bewildering was, “What do you want to do this summer? Do you want to get an internship? Where?”

That’s something students are not necessarily used to thinking about as part of their coursework. But for us, it’s very integral to have their project actually be helpful to them because it drives them in a way that nothing else can. It also just gives them a starting place to think about ideas.

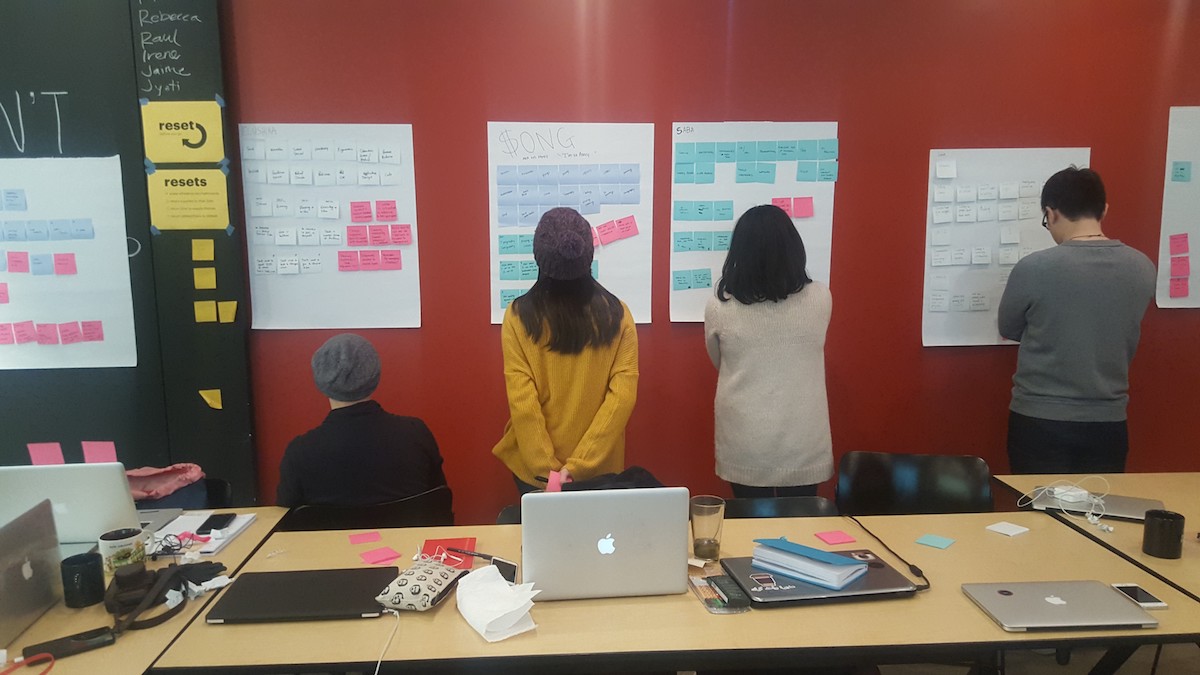

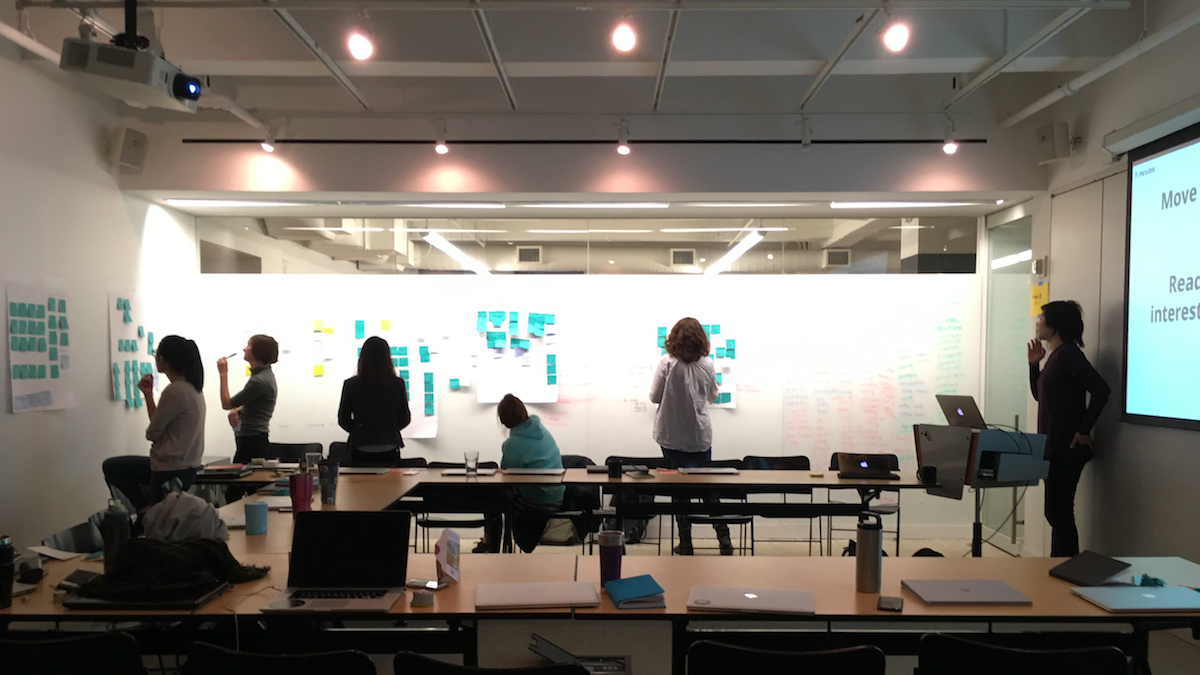

Students from the Class of 2017 (above) and the Class of 2018 (below) go through the ideation exercise at the beginning of the semester

G: The other key aspect was that it wasn’t a solitary exercise. We took them through multiple rounds where they would each look at and riff off each other’s work. I think that made it easier for them to get out of their own heads, and got the students involved in each other’s processes.

That’s where the ideas we talked about earlier come into play: it’s not enough to have a practice of momentum. To be successful, your practice has to incorporate other people.

If you don’t know a lot of people, adopting a default mode of working in public makes it easier for people—whether it’s your friends, your classmates, or your prospective fans or customers—to find you and come along for the ride as you develop your idea.

All of this is made easier the more you—in Nicole Fenton’s words—start with Words as Material. Whether it’s in the form of blogging, or via our more structured Working Backwards document, this is how you plant a flag and see who shows up.

The beloved GIF we use to explain what forward momentum can feel like

Embracing Constraints

G: So, most of what we’ve talked about centers on the students and what they need to do in order to be successful. As instructors, we’re limited to whether we’ve chosen good constraints for the course, which comes back to the $1,000.

C: When people hear constraints, they think that they’re something intentional and designed. But in this case, for the students it’s not about the constraints of the $1,000 format; it is about the constraints they discover because they are doing something in real life.

G: Please elaborate.

C: The $1,000 sounds like a constraint, but it’s actually a goal that comes with constraints. The real constraints are: students have to actually produce the Kickstarter rewards, students have to be able to launch a campaign by the end of the semester, and people have to really give students their money. Those are the constraints they have to design around.

G: Right, there’s a difference between designing something that you think is worth $1,000 and something that will actually result in people willingly giving you $1,000. Whether it happens or not is not fully within your control. And that can be scary because students have to have the willingness to be wrong and the willingness to operate under imperfect conditions.

C: Yeah, I think it’s the art of placing constraints in a way where you’re building an obstacle course that hints towards a set of outcomes. It’s game design, in a way.

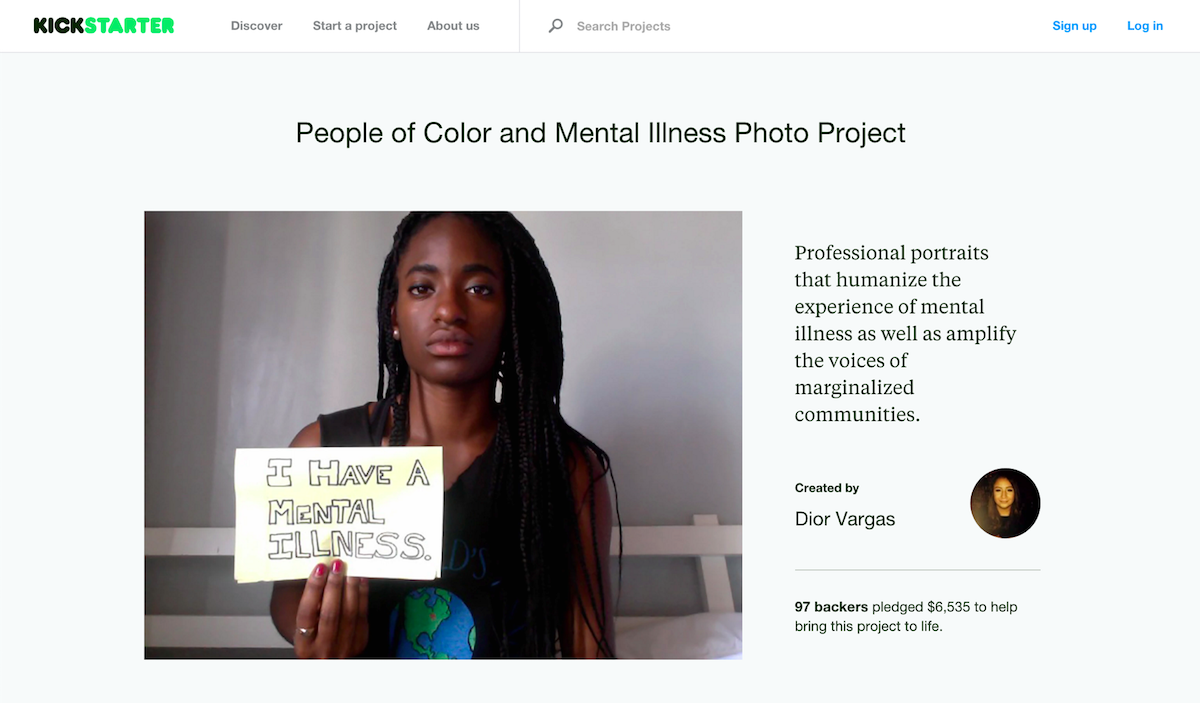

Dior Vargas expanded the scope of her previous work with the People of Color and Mental Illness Photo Project in the Orbital 1K

G: What do you think is the most impactful constraint in the course?

C: I think the most impactful constraint is time. No matter how much people are wiggling, they can’t get out of that one. When you’re three weeks out from launching your project, you have to think about what you can actually get done in three weeks and cut whatever elaborate stop-motion video you were going to shoot for the Kickstarter video—or power through it.

Time is also the element that’s missing from most speculative work. Speculative work is unbounded from real resources. You learn to dream up something big without having to think about how you will iterate your way there.

G: That seems to make sense to me. The very first year we taught the course, we lacked most of scaffolding that we have today, but what we did have was the constraint of the 15-week semester. Over time, we became more sophisticated and introduced achievable milestones.

C: It was really powerful seeing it in practice—especially in the Orbital 1K, where people had to launch in four weeks. There were a lot of times when I thought, “we didn’t give them enough time!” But the pressure made people do incredible things. And it was, in some ways, healthier than giving them too much time.

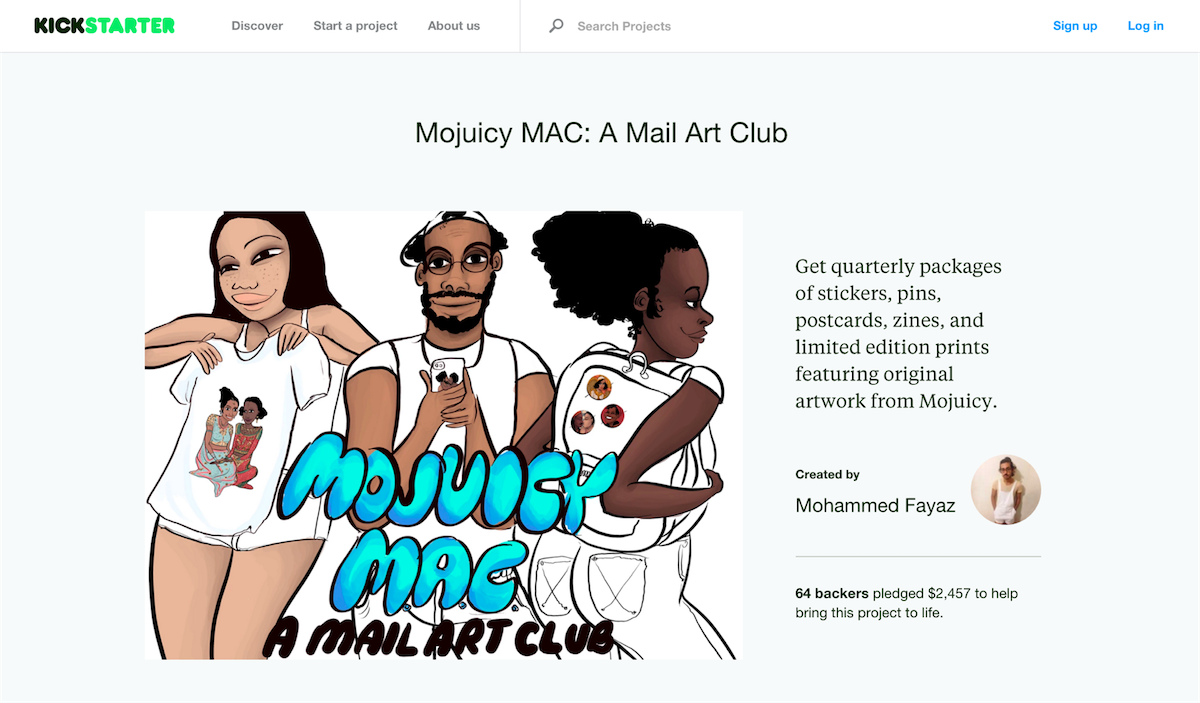

Mohammed Fayaz used the Orbital 1K to experiment with an alternative approach to build a business as an artist.

G: A semester might be too long.

C: Right. A semester tends towards long. Four weeks feels too short. But having the right amount of time pressure forces you to focus in a way that nothing else does.

G: Related to this, one of the critical success factors for the student is whether they land on an idea that they actually care about.

C: Why does that matter, do you think?

G: It’s hard to push through the pain and uncertainty of launching unless you are genuinely motivated. There’s just too much friction. Some of the friction is stuff like stamps and shipping labels, but the most challenging friction is the self-doubt.

It takes going through an experience like this to prove to yourself that you can do it, that you are capable of doing more than you previously thought.

Also, everything else we’ve talked about—the scaffolding—involves opening up and bringing other people into your world as collaborators, supporters, or coaches. You’re going to have an easier time convincing people to spend time with you if it’s clear to everyone that you genuinely care about your work.

C: On the other hand, I have also seen many people—maybe more people—who do genuinely care about their projects bail.

G: There are a lot of reasons why this may happen. You may care too much and be overwhelmed. You may be so invested in your idea that you’ll do anything to prevent its failure, including dragging your feet and sabotaging the project. Or, maybe it’s just not the right time.

All of this is part of the learning process.

Outcomes are out of our control. Nothing is guaranteed; we’re not entitled to success, and forward progress isn’t inevitable.

―Gary

But we get to decide where we spend our attention, and we get to define some of our constraints. And then you see how it goes. And then you adjust and try again.

These are simple concepts to explain, but you can’t really understand them unless you go through it yourself.

David Mahmarian and Kohzy Koh’s Designing for Autism

For a Post-Industrial World

C: One last thing I want to ask: what do you hope the students take away from the class? Of the things we teach, what do you hope infuses their work in the future?

G: I’ll be honest, in the first two years, I had more of an agenda in terms of what I wanted to see. I would say that’s all but gone now. This really has nothing to do with the students, but more with my own growth. Anyone who is a creator experiences a constant tension between control and chance. When I started teaching, I was much more control-oriented in my outlook. As I’ve gotten older, and as I’ve gone through this class more times, I’m less so.

Iteration 1 of Entrepreneurial Design (2012), with co-teachers Christina Cacioppo and Gary Chou, and guest speaker Khoi Vinh.

C: Right, you shared that with me when we started teaching together, and it’s been really important—that you can’t predict what people are going to take away. All you can do is lay stuff out for them, buffet style, and hope that they grab what they need. As teachers, we are in the role of showing them different paths forward.

But even if you aren’t control-oriented, there’s still a reason you’re teaching this class. You wouldn’t be teaching this class to have no impact, right?

G: What I want is for them to continue to be practiced at going out on a limb. Some of the hardest decisions they’re going to have to make as designers will be in cases where the right decision flies in the face of the data—or when there is no data that supports their view.

For example, if you look at Clay Christiansen’s Innovator’s Dilemma, the demise of some companies is actually caused by smart people making smart decisions. They’re doing exactly what they’re supposed to be doing, and that’s what leads to their demise.

So, what I want is for them to be able to think for themselves, and to get practiced at how awkward that feels. What kinds of interesting things could exist if individuals exercised the agency they already have? But it requires confronting uncertainty, and that is hard, even with the knowledge of having gone through the class. It's always going to be difficult, but you can become better at managing it.

The hard thing is there’s a real possibility that you will never get there, or that no one will care, or that it will never work. And these are things I continue to struggle with myself. But I’ve had to learn to accept that reality—it’s hard to know whether you’re just banging your head against a wall vs. making forward progress—and to also build the infrastructure to support it. That’s what Orbital is all about.

Networks are the infrastructure for resilience—the financial and emotional, but also the creative and intellectual.

―Gary

C: Yeah. For me, if we’re effective at what we are teaching, what we’ll start to plant into students’ heads is not just this literacy of how networks work and how to build and use them, but this greater awareness of all the networks around us.

If you push that to an extreme endpoint, what that means is—and this is gonna sound a little corny—that we’re all connected, and that you can’t adopt a zero-sum mindset. If you believe that you are only as successful as your networks, then you become incentivized to help your networks, and your networks’ networks, and so on. Eventually we’re all helping each other and not trying to maintain this very individualistic version of what success looks like. It changes this idea of being an independent creator—which historically has been so dominated by an egocentric and individualistic narrative—into something that’s more about building together.

G: Wow, that’s some pretty deep shit.

C: Yeah, man.

G: That’s a really elegant way to think about it. I’ve been thinking a lot about this question: “What does it really mean to be a citizen anymore?” There are all sorts of debates about the demise of the nation state and stuff like that but putting all of that aside, what does it mean to care about anything?

It’s clearly insufficient to just care about yourself, so I like the notion of tying your fate to that of the collective. As part of the collective, you would make very different design decisions. You would have to understand there are externalities—both positive and negative—to the decisions you make.

As designers, we’re not always conscious of the power that we wield or the position we design from. We’re sometimes so focused on optimizing a certain variable or metric—accomplishing a task that drives shareholder value. We’re not considering the collective, and you need to do that if you care about spending your time and energy on driving societal value.

C: Yeah. That’s a nice way of putting it—all things you need to be aware of as a designer in a post-industrial world.