Insights from Teach the 1K

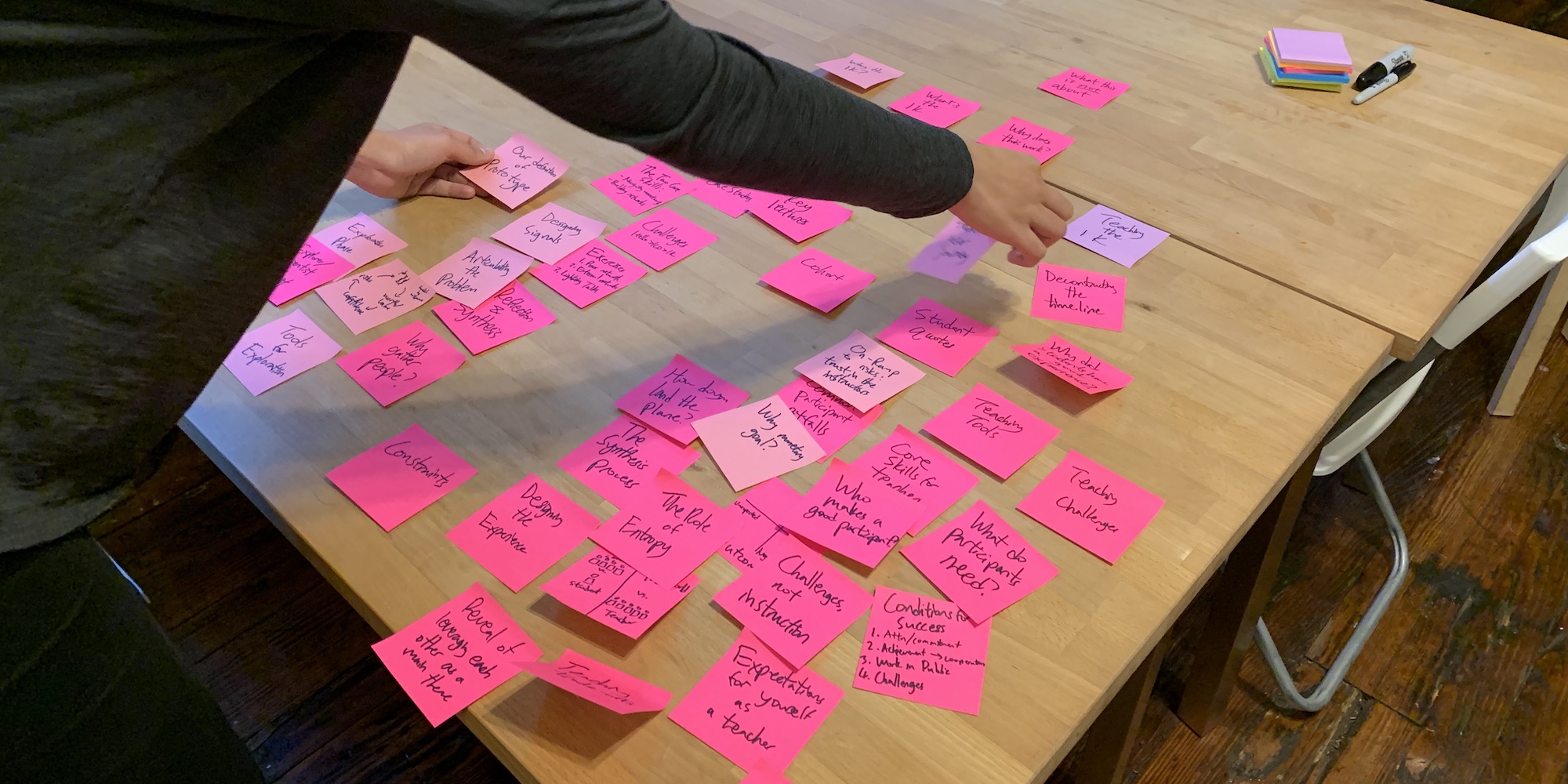

No post-it notes were harmed in the 10-month process of designing Teach the 1K.

Teach the 1K spans two substantive efforts:

- a multi-month process of review, synthesis and writing where we formalized our methods, vocabulary and frameworks

- the experience of running both the Workshop and Seminar for over 40 entrepreneurship educators and activators

Here's what we learned from both of these efforts:

1. There is a burgeoning interest in teaching people to confront uncertainty.

When we launched the Teach the 1K Workshop, we decided to frame it as an opportunity for teachers to learn how to teach people to confront uncertainty. We were concerned this framing might be too abstract and thus fail to attract sufficiently qualified participants.

As it turns out, that concern was unsupported. The response was so strong and clear that we created a second event to accommodate the demand.

In retrospect, this shouldn’t have been a surprise. We’re not the only ones to recognize the need for a different, more equitable, approach that is relevant to a broad range of creators, whether they’re optimizing for economic value or social value.

2. The heart of entrepreneurship is exploration, which is rarely taught.

The heart of entrepreneurship—no matter which flavor—is about navigating and confronting uncertainty. We refer to this as exploring, and it is distinct from training the labor force to work in the venture industrial complex.

Many of the existing approaches we have for fostering entrepreneurship are selection mechanisms intended to surface investment opportunities, not opportunities to teach people to explore. While there are efforts to coach and mentor entrepreneurs, the stakes are either too high, or the experience is conflated with the separate challenge of raising capital.

Generally speaking, people aren’t being taught to explore. Our current educational system is optimized for training people to climb ladders rather than to sail the open seas.

The fundamentals of how to explore can be taught in a consistent and repeatable fashion, but doing so is a distinctly different practice from teaching skill acquisition (especially at scale). Everything from the interaction model to the economics of what sustains such an effort needs to be carefully considered.

3. What makes the $1K Challenge an effective teaching tool is that it takes place in public.

Many lessons are best learned through experience rather than lectures, and this requires that the students pursue real projects with real consequences.

Unequivocally, we have found that it is this decision—that the students pursue a challenge with real-life outcomes outside of their control—that is the most critical enabler in teaching people to explore and confront uncertainty.

The $1K Challenge is an example of what we call In-Public Experiential Learning.

4. Online public spaces create new opportunities for In-Public Experiential Learning

The rise of online public platforms like Kickstarter and Twitter has resulted in an exciting arena for In-Public Experiential Learning.

By leveraging Kickstarter, for example, we inherit the constraints of the platform, which make it easier for someone to launch something as audacious as an original idea. We also benefit from the resources Kickstarter provides to any creator, not to mention the collective wisdom of past creators. Twitter creates a space where by the students’ projects can be discovered (or not) by a receptive audience.

In essence, Kickstarter is the boat, Twitter is the open sea, and our 16-week course provides the prompt (the $1K Challenge), the training, and a safe harbor.

Once the student launches, the outcomes are out of everyone’s control—which is a valuable lesson in itself. As a class, they’re going out to sea together and coming back with personalized lessons which inevitably benefit everyone.

This is just one example of an educational experience that is built on this new terrain. Done well, there’s a huge unrealized opportunity to create similar educational experiences across all online public space.

The hard part is figuring out how to craft the right challenge with a clear success or failure mode that encourages the student to willingly jump in, and the necessary safeguards for guiding participants to the endpoint with minimal risk.

5. In-Public Experiential Learning requires resilient instructional systems.

The experience of teaching an in-public challenge introduces an additional layer of chaos and complexity in the form of unpredictable student outcomes and obstacles.

This can be overwhelming for both the student and the teacher. By taking the students out of carefully controlled conditions, you are subjecting them to the entropy of the world, which can surface many irrational fears and reflexes. Similarly, as instructors, it's inordinately expensive to support a whole cohort of students working in this manner.

The key to managing this is to build resilient systems in lieu of defaulting to “hero mode”, where student challenges are resolved solely through increased individual effort by the teacher.

Such systems include things like:

- leveraging our own personal and professional networks for student project feedback,

- building software tools to automate mundane tasks, and

- establishing rituals where the students share some responsibility.

Thinking of teaching as a set of systems means that we can do more than just react; we can pre-empt problems, point out inefficiencies, and continually iterate.

6. The $1K Challenge is a specific implementation, not an adaptable framework.

Our hypothesis going into the workshop was that the $1K Challenge was one of the best ways to actually teach people to explore and confront uncertainty, and that other educators could potentially modify it to fit their contexts.

In reality, it would be more effective to teach other instructors at the level of abstraction right above that.

The $1K Challenge has worked well for us because over the years, we tailored it precisely to our context—teaching first-year graduate students in the SVA IxD MFA program. We built a precise obstacle course that accounts for our students’ strengths and weaknesses—as well as our own—and considers the constraints and the institutional context in which we operated. The process we have shared here is the outcome of seven years of optimization.

While there are many components of the $1K Challenge that can be borrowed or adapted, it’s ultimately too custom-built to serve as a starting point for other educators and activators, especially those working in very different contexts.

Rather than teach the $1K Challenge, the more impactful (and scalable) approach may be to share what we know about designing and operating In-Public Experiential Learning programs, and to help people create programs customized to their context—whether they’re coming from academia, government, non-profits or for-profits.